Feature Assuming the weather and engineering gods cooperate, a US government-funded satellite dubbed Moonlighter will launch at 1235 EDT (1635 UTC) on Saturday, hitching a ride on a SpaceX rocket before being releasing into Earth’s orbit.

And in roughly two months, five teams of DEF CON hackers will do their best to successfully remotely infiltrate and hijack the satellite while it’s in space. The idea being to try out offensive and defensive techniques and methods on actual in-orbit hardware and software, which we imagine could help improve our space systems.

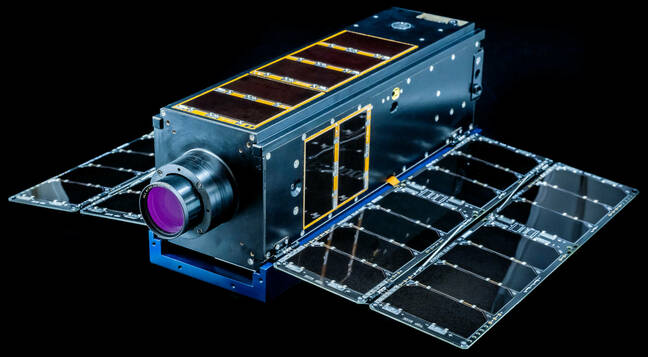

Moonlighter, dubbed “the world’s first and only hacking sandbox in space,” is a mid-size 3U cubesat [PDF] with a mass of about 5kg. Stowed, it is 34 cm x 11 cm x 11cm in size, and when fully deployed with its solar panels out, it measures 50 cm x 34 cm x 11 cm.

It was built by The Aerospace Corporation, a federally funded research and development center in southern California, in partnership with the US Space Systems Command and the Air Force Research Laboratory. It will run software developed by infosec and aerospace engineers to support in-orbit cybersecurity training and exercises.

This effort was inspired by the Hack-A-Sat contest co-hosted by the US Air Force and Space Force, now in its fourth year at the annual DEF CON computer security conference.

The goal of Moonlighter was to move offensive and defensive cyber-exercises for space systems out of an on-Earth lab setting and into low Earth orbit, according to project leader Aaron Myrick of Aerospace Corp. Not only that, but the satellite needs to be able to handle multiple teams competing to seize control of its software without losing or damaging the whole thing and ruining the project. Thus, an onboard sandbox approach was taken.

“If you’re doing a hacking competition, or any sort of cyber activity or exercise with a live vehicle, it’s difficult because you’re potentially putting that vehicle’s mission at risk,” Myrick told The Register.

“And that’s not a good option when you’ve spent a lot of engineering hours and a lot of money to get this launched. So we said if we want to do this right, we have to build this from the ground up.”

Sending to outer space … The Moonlighter satellite. Click to enlarge. Credit: The Aerospace Corporation

To this end, the small satellite runs a software payload that behaves like a real flight computer, which can — hopefully! — to be subjected to multiple, realistic attacks and commandeered without underlying critical subsystems being affected.

“This allows cyber experiments to be repeatable, realistic, and secure, while maintaining the health and safety of the satellite,” as Aerospace Corp put it.

Moonlighter’s first test will come in August when it will be part of the Hack-A-Sat 4 competition in Las Vegas. Five teams qualified for the contest’s final at DEF CON, during which they’ll get a crack at the bird.

This year’s annual competition will thus be the first time conference hackers get to test their skills against a live, in-orbit satellite. The top three teams will win a monetary price: $50,000 for first place, $30,000 for second, and $20,000 for third.

Space Jam

James Pavur, lead cybersecurity software engineer at Istari, participated in the three earlier Hack-A-Sat competitions, and gave a talk on radio frequency attacks in outer space at last year’s DEF CON.

He describes himself as a “passionate security researcher” when it comes to poking holes in satellites, and did his PhD thesis at Oxford on securing these kinds of systems. You also might remember him from his exploitation of GDPR requests.

Pavur participated in the qualification round for this year’s satellite hacking competition, though didn’t make it to the finals.

The qualification round included “wicked-hard astrodynamics problems related to overall mechanics and positioning, figuring out where objects in space will be, and where they are going,” he told The Register. “It’s a lot of really deep mathematics on the physics side of things, and it requires a lot of expertise in embedded systems and reverse engineering.”

Space systems … are always under a degree of environmental attack that we’re not really accustomed to

There are a couple of things that make securing space systems unique, he explained.

“The most obvious is you can’t just go up there and reboot them,” he said. “So your risk tolerance is very low for losing access to communications to the device.”

Because of this, space systems are built in a risk-averse way, and employ redundancy to provide multiple communication pathways to recover a system if it fails, or to debug equipment that’s malfunctioning.

These pathways, however, also give miscreants more opportunities to gain access to, and ultimately compromise, a satellite. “They can all become attack surfaces that an attacker might target,” Pavur said.

Priorities

“The other big thing that makes space systems different is that they’re always under a degree of environmental attack that we’re not really accustomed to,” he added.

This includes physical threats, such as solar radiation, extreme temperatures, and orbital debris.

“So when people build space systems, and they’re deciding which risks to prioritize, they’ll often treat cybersecurity as a lesser risk against the absolutely certain aggressive environmental harms,” Pavur explained.

“They’ll make choices around costs and priorities that deprioritize cybersecurity concerns and elevate physical concerns.”

That’s not always a bad choice, he added, it’s just not a choice we typically have to make with ground-based networks and nodes. And it’s one of the reasons why space systems have struggled to keep up, cybersecurity wise, with their Earthly counterparts.

Then there’s the growing commercialization of the aerospace industry, coupled with hardware and software used in space becoming increasingly commoditized and mass manufactured, not unlike the tech used in ground-based systems.

“The bar is being lowered for entry to space,” Myrick said.

“And that’s both for people that are trying to put things there but also for people that are willing and able to make other people have a bad day,” he continued, using last year’s Viasat debacle as an example of “a pretty destructive event that made people have a very bad day.”

“With Moonlighter, we’re trying to get in front of the problem, before it is a problem.”

Space security is national security

To be clear, Russia’s cyberattack on Viasat’s Ukrainian satellite broadband system — which knocked out service for tens of thousands across Europe as Putin’s army invaded its neighboring county — began with an intrusion into the company’s satellite ground infrastructure.

“But they used the satellite network to deploy, which is important,” Myrick said. “It highlighted the issue, and made it so it’s not theoretical.”

For many, both in government and the private sector, the Viasat security breach moved the issue of cybersecurity in space away from the stuff of sci-fi novels and into reality.

“We are all aware that the first ‘shot’ in the current Ukraine conflict was a cyberattack against a US space company,” acting US National Cyber Director Kemba Walden told reporters at the RSA Conference in April, en route to the White House’s first space industry cybersecurity workshop.

Defending space systems against threats remains “urgent and requires high-level attention,” Walden said.

Space geeks and hackers

Still, the space industry hasn’t been the most welcoming of security researchers, even ethical hackers looking to find and disclose bugs before the baddies exploit them.

Pavur said he hopes Moonlighter will encourage more “acceptance of offensive security research,” in the aerospace industry. This could include companies offering bug bounties, hosting hacking competitions, or hiring penetration testers to stress test their systems.

“Hopefully a project like Moonlighter will get the industry thinking about ways they could apply the fact that space is really cool and fun, and that hackers are interested in it,” he said. “There are lots of incredibly talented security people who would like to make the space world more secure.” ®

Moonlighter is set to launch Saturday from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket carrying supplies and equipment to the International Space Station. A live-stream of the lift-off should appear here.